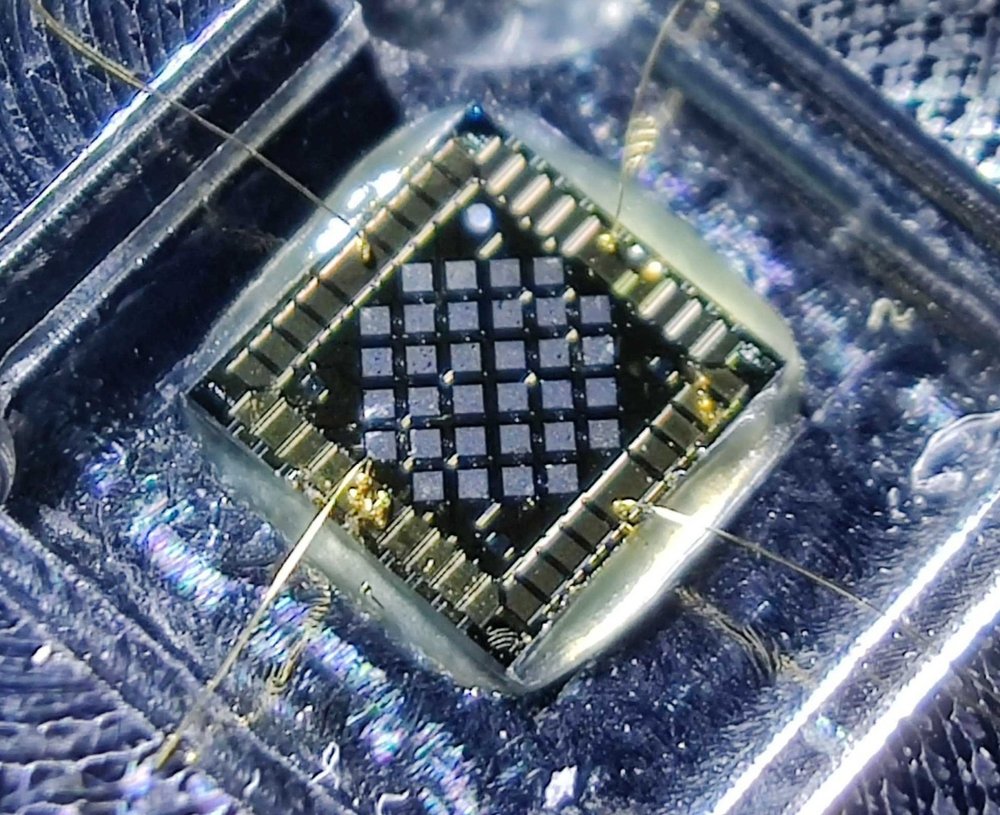

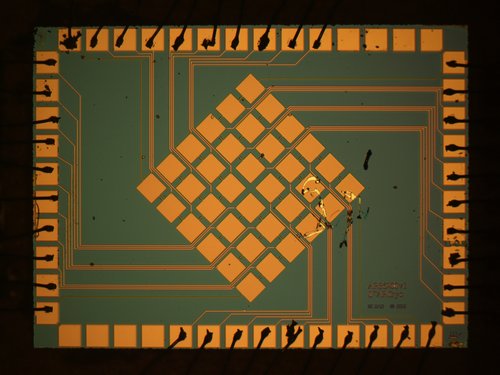

(A Superconducting Tunnel junction array / credit: BeEST collaboration)

Neutrinos are some of the most mysterious particles in the universe. They are incredibly small, invisible, and rarely interact with anything – so much so that they are often called “ghost particles.” Despite their abundance in the cosmos, and their potential role in persistent cosmic questions like the nature of dark matter, we still don’t fully understand how neutrinos behave at the quantum level.

However, the Beryllium Electron capture in Superconducting Tunnel junctions Experiment (BeEST) collaboration is leveraging TRIUMF’s rare isotope beam capabilities to delve deeper into the neutrino by exploring its interaction with implanted isotopes, shedding new light on how neutrinos interact with matter.

In a new paper published in Nature, the BeEST collaboration has made a significant step forward in establishing boundaries for a critical parameter of the neutrino – a property called the neutrino wavepacket.

To understand this discovery, we need to learn a bit of background information about neutrinos.

Catching the wave(packet)

The elusive neutrino is one of a few fundamental constituents of the Standard Model of particle physics – our best framework for explaining how the building blocks of matter interact.

Importantly, neutrinos are also the most abundant particles in the universe that have mass. Yet, despite their abundance, neutrinos are incredibly difficult to study. They rarely interact with other particles, making them elusive and hard to detect. This unique property makes neutrinos an interesting subject for scientists trying to understand the fundamental rules of the universe.

There are so many open questions about the nature of the neutrino, including understanding their quantum properties such as the size of their wavepacket.

In quantum mechanics, particles like neutrinos don’t have a definite location or speed. Instead, they exist as a wave that can be spread out across space. This spread is called a ‘wavepacket’ —the spread of their position and momentum, represented as a group of superposed waves which together form a traveling, localized disturbance. The bigger the spread, the less we can determine about the particle’s exact position or momentum

The neutrino wavepacket specifically is very difficult to study in detail due to the nature of neutrinos: they have very low mass, lack electric charge, and only interact via gravity and the weak interaction. As such, in most neutrino experiments, scientists use large detectors that observe how neutrinos interact with matter. However, many such detectors struggle to measure the finer details needed to confine the parameters of the neutrino wavepacket.

This is where experiments like the BeEST show tremendous promise.

Ghost-particle, meet BeEST

The BeEST collaboration is using a clever, novel technique to move past the limitations of directly measuring neutrinos and instead measure the ‘recoil’ of an entangled system of an atom and a neutrino – specifically the daughter of beryllium-7, llithium-7, and an electron neutrino (ve), two products that result when beryllium-7 undergoes a process called electron capture nuclear decay.

When beryllium-7 decays, the emitted neutrino is entangled with the emitted daughter lithum-7 atom, meaning they share certain properties in a way that allows researchers to study both at the same time. Further, researchers can leverage the fact that energy and momentum must be conserved across the decay and emission process – meaning that they can reconstruct with some precision the unknown energy of the neutrino by measuring the known recoil energy of the lithium-7. By measuring the energy of the recoiling lithium-7 nucleus, scientists can learn about the size of the neutrino’s wavepacket.

In the experiment described in the paper Direct experimental constraints on the spatial extent of a neutrino wavepacket, published in Nature, the research collaboration describes a highly advanced technique that involves implanting beryllium-7 produced using TRIUMF’s ISAC facility into superconducting sensors (superconducting tunnel junctions, or STJs). The implanted sensors were then transported to Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory to perform the high precision measurements at a temperature of just 0.1 Kelvin. At this incredibly low temperature, a final-state energy spectrum for the decay products could be obtained.

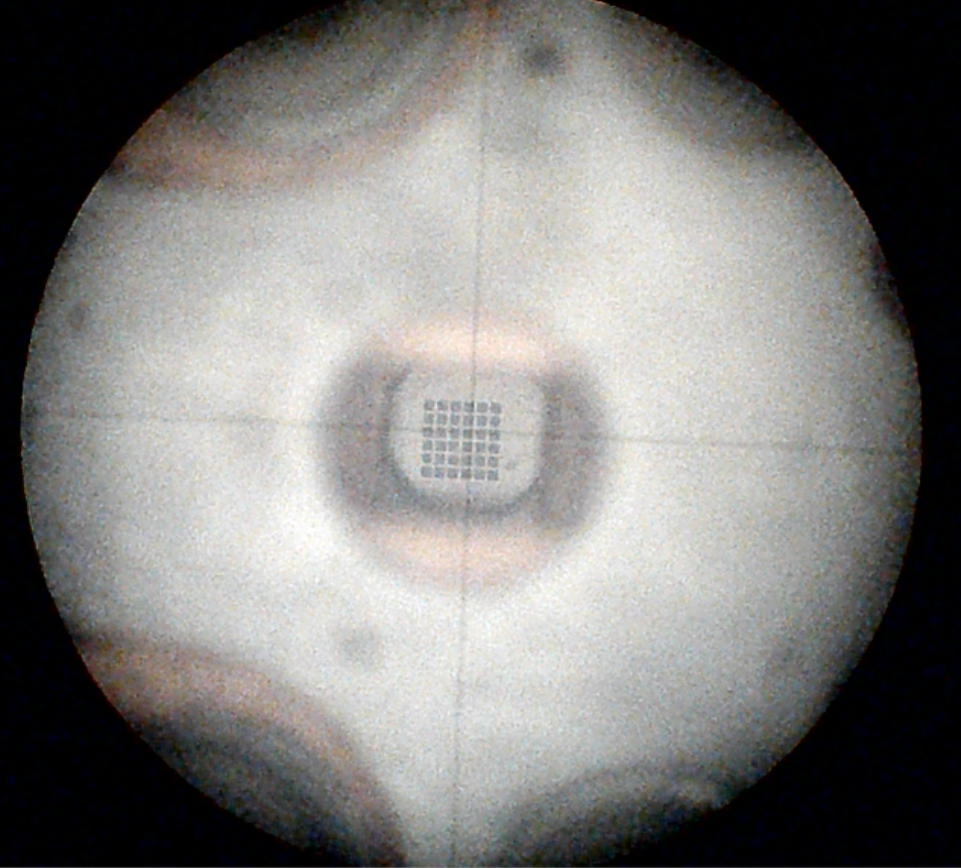

Targeting a rare isotope beam of beryllium-7 to implant into the BeEST STJ array at TRIUMF / credit: BeEST collaboration

The results? The BeEST researchers were able to measure the energy of the recoiling lithium-7 atom with incredible precision. They discovered that the size of the neutrino’s wavepacket is larger than expected, with a lower limit on its spatial extent of about 6.2 picometers (a picometer is one trillionth of a meter!).

This finding is the first direct measurement of the lower limit of a neutrino’s wavepacket and sets a critical constraint on how these particles behave.

“This is a very exciting era in subatomic physics research,” said Annika Lennarz, TRIUMF Associate Research Scientist. “We are just beginning to explore the full capabilities of the BeEST experiment and how this unique technique will advance our understanding of the nature of neutrinos and, potentially, physics beyond the Standard Model.”

Nature of the BeEST

The BeEST experimental technique shows tremendous promise to help refine our understanding of neutrinos and their role in the universe; neutrinos are not just fundamental to understanding the Standard Model of physics, but also have connections to other mysteries, like dark matter and the potential existence of new types of particles. By measuring the neutrino’s wavepacket, scientists may soon be able to test competing theories about how neutrinos behave and even challenge existing models of particle physics.

Congratulations to the BeEST team and our TRIUMF collaborators!